To coincide with the exploration of sub-glacial Lake Ellsworth in Antarctica this winter Millennium Court Arts Centre presents Crystalline, an exhibition of work by both internationally known artists and local practicing artists, graduates & postgraduates living or working throughout Northern Ireland. The exhibition incorporates pieces submitted through Open Submission and by invitation, and the work explores the twin themes of scientific endeavour and the landscape of Antarctica, the latter of which has proved unfalteringly seductive to artists. Working in various disciplines the artists represented in Crystalline cover many facets of Antarctic exploration, teasing out aspects of the barren terrain, seemingly devoid of colour, sound and life, and the inverted sub-glacial landscape below the surface.

The Frozen Laboratory: There is a powerful trope associated with Antarctica portraying it as blank, politically neutral, pristine territory. It is free from a history of warfare and turmoil. Its environment is uncompromisingly resistant to permanent human habitation and colonisation. In 1959 the Antarctic Treaty was signed making the entire continent a science reserve and ensuring that no one country could claim sovereignty. Antarctica may therefore be viewed as the world’s largest living laboratory. Lake Ellsworth, which is the site for drilling by a British team this winter 2012, lies beneath the continental ice sheet in West Antarctica and it is hoped that the ancient water therein will reveal information about the earth, life and the environment.

Time in the Antarctic is generally comprehended in geological epochs rather than by human timescale. Roy and Kathryn Nelson examine this concept through materials and processes that demonstrate a physical accumulation of time. Belinda Loftus’s work references the extreme conditions for life in Antarctica while Joanne Proctor’s drawings obliquely point towards the origins of life and by extension the idea that exploration may yield new discovery. It is thought that conditions in Antarctica’s subglacial lakes may demonstrate how microbial life can exist in extreme conditions, similar to those on other planets and moons in the solar system. David Hamilton’s paintings seem to point both to the cosmos and the ice sheet.

As a counterpoint to the celebratory nature of scientific discovery Heather Fleming’s work looks at the mechanics and practicalities of endeavour in a harsh environment, the fleeting traces through snow and ice and the covert scramble for resources (in this case oil). This complicates the neutral laboratory by suggesting that scientific knowledge and technology may be appropriated for commercial gain.

Works by Dorothy Cross, Jana Winderen and Ruth le Gear represent art made on location in extreme conditions. Cross’s monochromatic film piece, rendered in negative, shows a group of deep sea divers in the icy, crystal waters of Antarctica. Her work also seems to reference the early history of human exploration in the Antarctic, motivated by commerce through hunting of seals and whales. This precipitated the later age of heroic exploration (1895-1917) in the continent, an idea explored in the paintings of Damien Flood. Before it was mapped and charted Antarctica was a place between fact and fiction (Terra Australis Incognita), speculated about since the second century but not seen until the nineteenth. Flood’s fantastical landscape paintings reveal his curiosity about these expeditions, and the struggles and hardships that accompany voyages in search of undiscovered, foreign or otherworldly landscapes.

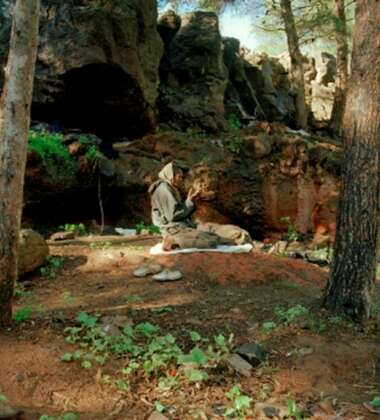

Through sculptural assemblage Shelby Woods reflects on the inhospitable landscape as the ideal location to gain objectivity on the human condition, on loneliness and mortality. Similarly through painting Anna Marie Savage probes the state of solitude. Antarctica, perhaps due to its ‘blankness’ and sublime landscape is also a tabula rasa on to which imagination is projected. Claire Muckian’s micro-scale sculptural work is derived from satellite imagery of subglacial lakes and posits the lake as a metaphor for creativity – hidden pockets of imagination in everyday contexts. Mark Joyce’s paintings meanwhile revel in the crystalline sharpness of light in a cold climate, inspired by time spent in Iceland.

Jana Winderen’s work merges with scientific research – using advanced sound recording technology Winderen records in crevasses of glaciers, in fjords and in the open ocean of the frozen north. Weaving together these hidden sounds into complex soundscapes she reveals the rich complexities and strangeness of the world beneath. Ruth le Gear, who recently completed a residency in the Arctic Circle (another extreme environment), is strongly attracted by the scientific method behind investigation of non-physical phenomena and conversely the requirement of investigating fictional scenarios to understand more about the self – ideas she explores in these two exhibited films.

Dorothy Cross, Antarctica shown by kind permission of the artist and the Kerlin Gallery, Dublin. Mark Joyce and Damien Flood shown by kind permission of the artists and Green on Red Gallery, Dublin. Jana Winderen, work used with kind permission of the artist and publisher Touch Music.

Irish Times Review (4 Jan 2013): Exploring Sublimely Ridiculous Antarctica by Aidan Dunne